What Is Customer Discovery for?

Balancing the known unknowns and the unknown unknowns

It’s not just about learning what you don’t know; it’s also about learning what you haven’t even imagined.

Customer discovery is a process used by entrepreneurs and businesses to identify and understand the needs, behaviors, and pain points of their potential customers. By conducting customer discovery, businesses can gain valuable insights into their target market and use these insights to refine their product or service offerings. Most people who have studied the topic, or who already practice customer discovery in the field, understand this definition, but even some of those people can lose sight of the fact that customer discovery is also about uncovering insights about what you don’t even know you’re supposed to have a stance on. So, you’re not only validating your own hypotheses, but also opening a broader discussion of the problem space to uncover insights implicitly left out of your conceptualized business and its many presuppositions.

When the Ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes’ bath tub overflowed, he discovered that he displaced water with respect to his body’s own volume. He didn’t already have that as a hypothesis, but rather happened upon his eureka moment in the course of going about his day. Similarly, in customer discovery some of our discoveries come about outside of hypothesis-driven experimentation. Sure, we’re more intentional about our one-on-one conversations during customer discovery than Archimedes was as he hopped into the tub (and we’re also not typically prompted to run naked through the streets of Sicily with each gathered insight), but we keep those conversations open-ended enough to understand things that we didn’t set out to learn explicitly.

Hopefully this makes conceptual sense to you, but a couple examples might help to drive the point home.

Imagine a B2B company developing a new software platform for managing employee benefits. Through customer interviews, they discover that many HR managers are overwhelmed by the amount of paperwork involved in managing benefits, but the are hesitant to switch to a digital platform because they were concerned about data security. This led the company to focus on developing a highly secure platform to give HR managers peace of mind while also simplifying the benefits management process. If they had instead narrowed the focus of their conversation to the minutiae of digitalization and automation alone, they would have missed out on a key customer need embedded within the the status quo process.

Next, imagine a startup developing a mobile app that would help users find and book fitness classes. Through customer interviews, they discover that many users are actually more interested in finding workout buddies than booking classes, which led them to pivot their product to focus on social connections within the fitness community. If they had focused solely on innovating within the booking use case, they would have missed the customer’s much deeper desire to connect with their peers one on one.

It’s important to note that stumbling upon these unforeseen insights in customer interviews is no foregone conclusion. While it’s no easy task to create an effective discovery script, the core principle of conducting open-ended interviews rather than closed-ended ones is a pretty good guide post. Borrowing from the Design Thinking concept of “divergent” and “convergent” thought and activities, the discovery process should skew heavily toward the divergent end of the spectrum. However, it’s easy to fall victim to your own biases and instead think divergently only within the bounds of your own thoughts. Instead, you need to think more broadly about the problem space and the needs, pains, and gains of your customer. To illustrate this point, in the figure below notice the seemingly unlimited divergent options within the the constraints of a hypothesis taken from fitness example from before. If you’re in that blue cone looking forward, you see a limitless landscape of expanding opportunities, but it’s a form of tunnel vision where you’re missing a “bigger infinity” defined by the broader space in red.

Notice how the questions in the inner cone differ from the broader questions in the outer cone. The more specific questions, while crucial to the validation of your hypotheses, would ideally come later in your interview so as to not bias the broader questions that may otherwise yield unexpected insights.

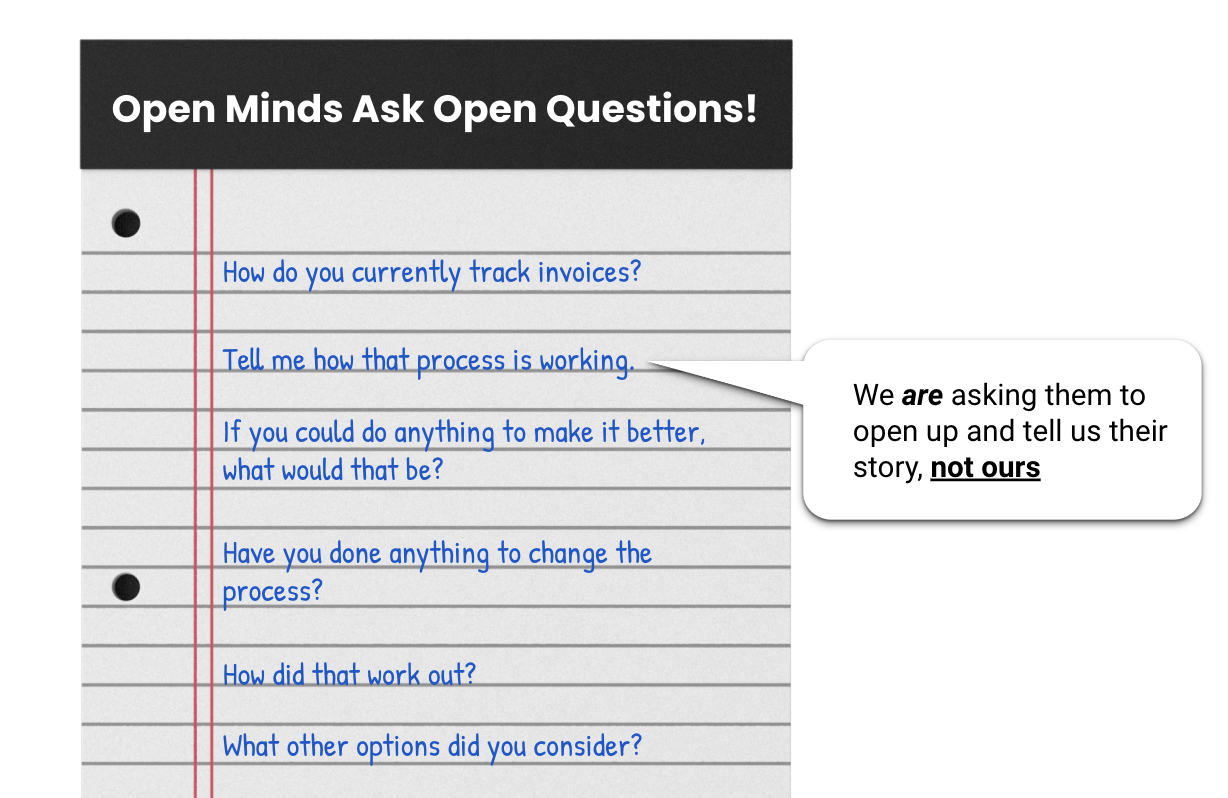

Also, for perhaps a more tangible visual, look at the script below and see how many questions you can open with before getting to explicit validation of specific hypotheses. Open up the conversation and let the customer define what’s meaningful before inserting your own biases.

Start with the general before drilling down into specifics.

Serendipity may not sound like a great business strategy, but the process of customer discovery is a tactic that will put you in position to capture those eureka moments. You may not like the idea that some of your best innovations will come from someone else’s words rather than from yours, or from a formula that you’ve concocted, but if you’re in the game of innovation and entrepreneurship ambiguity simply comes with the territory. Or, if you’re a large enterprise aiming to be customer-centric, there’s an inherent conflict with customer-centricity and actively limiting customer input.

In closing, I’ll leave you with some real-life examples of serendipitous product discoveries. They weren’t all the result of customer discovery, but they’re nonetheless an homage to the value of learning what you don’t know you don’t know.

🤞 Great products that were discovered in part by accident 🤞

- Post-it Notes: Invented by a 3M scientist who was actually trying to create a stronger adhesive

- Viagra: Originally developed as a treatment for high blood pressure, but found to have a surprising side effect.

- Play-Doh: Originally marketed as wallpaper cleaner, but was later discovered to be a popular toy when children started playing with it.

- Penicillin: Discovered by Alexander Fleming after he noticed that a mold had contaminated one of his petri dishes, killing the bacteria on it.

- The microwave oven: Invented by Percy Spencer when he noticed that a candy bar in his pocket melted while he was working with radar equipment.

- The slinky: Invented by Richard James who was trying to create a meter designed to monitor power on naval battleships, but accidentally knocked over a spring and watched it “walk” down a stack of books.

- Chocolate chip cookies: Ruth Wakefield, who owned the Toll House Inn, was making cookies and ran out of baker’s chocolate, so she substituted with broken pieces of Nestle chocolate, hoping it would melt and spread throughout the dough. Instead, the chocolate held its shape and the chocolate chip cookie was born.

- Bubble wrap: Invented by engineers Alfred Fielding and Marc Chavannes who were trying to create a textured wallpaper, but the product was unsuccessful. They later found that the air bubbles in the material made great packaging material.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tom Carmona is an experienced entrepreneur, investor, and operator. Prior to joining ID8, Tom was Managing Director at Symphony Alpha Ventures, where he oversaw early-stage investments in enterprise SaaS, healthcare IT, and healthcare services. Tom holds an MBA with a specialization in entrepreneurial management from the University of Wisconsin and lives in Nashville with his wife and three children. Before entering the business world Tom completed both the Peace Corps and Teach For America programs. In his spare time he enjoys arguing about NBA history with his friends.

Ready.

Set.

Innovate

We’d love to put our experience with Fortune 500 companies to work for you